José featured in San Francisco Classical Voice

José Navarrete Mazatl Finds Art in Community

by Lou Fancher

June 15, 2021

Para Español, desplazarse hacia abajo.

日本語はページ下部にあります。 スクロールしてご覧ください 。

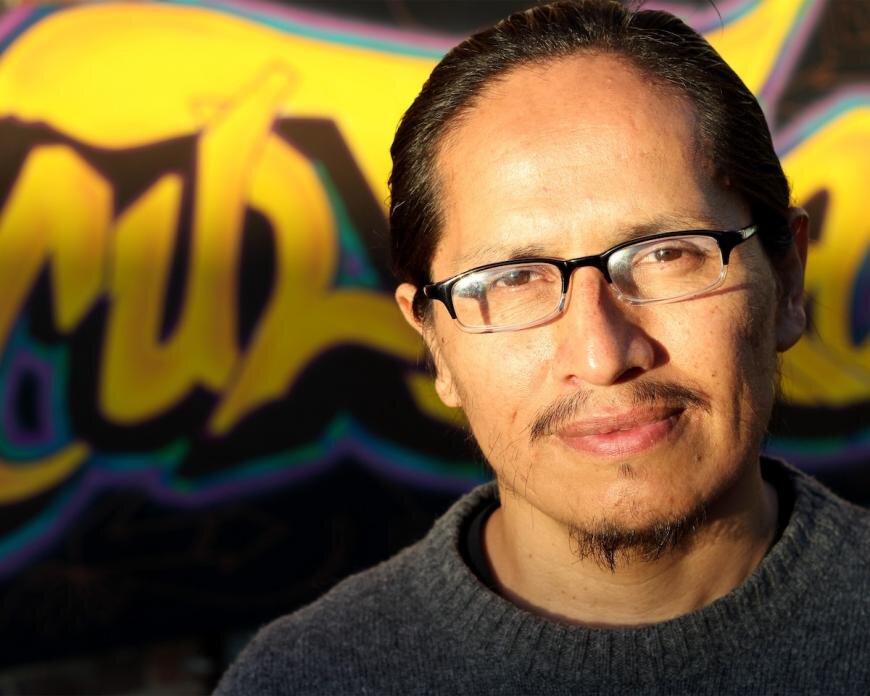

José Navarrete Mazatl

It is early June 2021 when José Ome Navarrete Mazatl and I manage to arrange a phone conversation. We last spoke in December of 2019 about the 2020 FRESH Festival and a weekend of performances he co-curated featuring Black female dance artists and activists. Now, he is in his native Mexico City, where spotty internet reception and restricted cell phone range require extra travel and other strategic moves to make our call possible. When we finally connect, we marvel at the eerie pandemic paradox of “it has been an eternity” versus “that happened just yesterday, didn’t it?” While more than a year without live performances has passed and seems like a lifetime ago, memories of the FRESH Festival remain unfaded and, we agree, are “just a blink away” in our minds.

Navarrete Mazatl is a multidisciplinary artist whose work centers on social justice. He founded and co-directs with Debby Kajiyama NAKA Dance Theater, a collective that creates experimental performance works and develops collaborative, community-based multidisciplinary projects drawing upon history, folktales, mythologies, rituals, and most presciently, current social justice issues.

NAKA Dance Theater's Debby Kajiyama and José Navarrete Mazatl in Amorando | Credit: RJ Muna

This month, Navarrete Mazatl is continuing a years-long project with MUA (Mujeres Unidas y Activas), a group of Latina women who advocate for legal rights for domestic workers and support survivors of domestic abuse. And keeping the collaboration with MUA going hasn’t been Navarrete’s only good fortune during the pandemic. In 2021, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship as a choreographer, marking a career pinnacle he says was entirely unexpected because his work is not “beautiful choreography presented in an opera house.”

Striking a far different, tragic, and personal note, Navarrete, as we begin our conversation, reveals that during the pandemic he has — while not unappreciative of the honors and opportunities received — encountered immense, immeasurable loss. His mother succumbed to COVID-19, and his words on the impact it is having on him personally and professionally echo long after our phone call concludes.

NAKA Dance Theater's José Navarrete Mazatl and Debby Kajiyama with members of Mujeres Unidas y Activas | Credit: Scott Tsuchitani

Let’s start with talking about significant aspects of your experiences during the pandemic.

Oh dear. So big. I lost my mother during the pandemic. That was a powerful, emotional, devastating thing for me. It was COVID, yes. That’s how the pandemic affected me. We had a strong relationship, long, very open, vast. I’m mentally having a departure [from that] which has allowed me to contemplate mortality in a new way. All these people we love and who are extremely important in our lives are no longer with us. I’ve been navigating these times we are living. These are reflections about me. I grew up 20 more years in the moments after my mother left. With that departure, one everybody will face, it is a way of finding a new way of navigating in life. There are different levels of coping.

In terms of my work with these women during this time — these Latina immigrant women who pursue the empowerment of domestic workers in the Bay Area with Mujeres Unidas y Activas — I’m here in Mexico because of a project started three years ago where we investigated the phenomenon of disappearing, of forced disappearance. During the process of creating that piece we were connected with families in Mexico.

What is this work you are doing in Mexico City generating for you internally?

For me, the role of women in my life is very strong and connected to my mother. My mother was powerful, and I do feel that is the permission I have to work with MUA. Being a survivor of domestic violence — I saw my mother attacked and saw her being punched and attacked during domestic violence between my father and my mother — that is the relationship and my connection with MUA. I am trying to incorporate that experience with art as healing, as self-care for domestic abuse. I am using movement, theater, poetry, to raise visibility of this particular group. I am interested in my relationship with this community because I wanted to understand the intersection between contemporary art, social justice, and community. All three elements I am looking at: I’m using artistic tools to elevate the empowerment and visibility of Latina women.

Let’s leap to an entirely different mountain top: the Guggenheim Fellowship. How were you contacted and what initial thoughts arose?

It was a big surprise because I never expected to get that award because of the work I do. It is not traditional contemporary dance. I use tools of choreography, but I’m usually working with non-dancers, non-actors. I’m not creating beautiful choreography presented in an opera house. I’m not interested in that. How can I use my artistic trajectory to advance a particular community, perhaps a community that is in the marginal places of society? That is what I’m interested in.

Does that mean the definition of choreography is changing?

The concept of choreographing is changing. Ideas about movement are opening up, the source of expression comes in a different way. When I found out [about the Guggenheim], I thought, “Oh my god, they gave it to me.” I have seen in the last few years and this is an indication that they are supporting artists and choreography that are not works for or by a dance company or traditional theater group. It was funny; I first got an email that said they thought I was a finalist, however the board needs to approve it so please don’t say anything. We are not done deciding and you might be awarded. They seemed not secure yet. In the second email, they said I was awarded. It was like you might … then the second email saying you get it.

What was most important for you to include in your application?

Working with this group of Latina immigrant women. It was creating raw performances based in the testimonies of Latina women living in the United States. That was my proposal. I had a lot of video materials that reflected the work I am doing with that particular group, so I didn’t need details to explain it. The work is powerful, and in the videos, you can see the emotional, invigorating empowerment of these women. They are super strong and helping their own communities.

NAKA Dance Theater's José Navarrete Mazatl and Debby Kajiyama with members of Mujeres Unidas y Activas | Credit: Scott Tsuchitani

What questions would you like to ask, or which social justice issues will you choose to address, in new work during the next few years?

Definitely the relationship with women and other genders is important to me. Having a balanced understanding is important. It reflects how we interact with our environment. I feel concerned by gender violence. I get overwhelmed, and I try to figure out myself as an artist and what I will do. It reflects on how we relate to our community, our family, how we treat our water, our land — all those things we de-attach from because of the ways we are living. We don’t understand where things come from. Especially our food. We don’t have that concern because everything is given to us. We need to know, because nurturing things have to do with Mother Earth, with our mothers, with women, the environment.

Gender violence and detachment: What working practices have you found to address those separations?

One of the things I’m thinking about is how can I self-care? I get super inspired and then I don’t have the capacity to do all I think of. I get overwhelmed and tired. I have to take care of myself and my main collaborators. Do we need to slow down? Can we use this idea of everything being overwhelming — the pandemic, the climate is horrible, the gender violence is horrible. How is our work affected? Using the radical act of slowing down, that is something I deeply need to do to embody myself.

It is OK to slow down, but also, I must be extremely clear in my intentions. That has to do with contemplation. There needs to be another way to interact. We are so busy we don’t allow ourselves to say no. If I can find magic in one simple thing that allows me to impact something, to plant a seed and hope it will flourish — slowing down is important to achieve that. I’m trying to figure out during the pandemic who in the community needs a specific thing, like food. That shifts my priorities.

What will being a choreographer mean or entail in the next two to five years?

I choose and I like to look at dance that has relationships. I am looking for people of color, artists that connect contemporary art and social justice. That draws my attention. Without that context, I’m not interested. I’m looking at dance in a very particular lens. A lot of amazing artists need support. I get excited because this is the next generation. My choreography is tailored in a particular way. I don’t watch ballet at this time. Except there is a [Canadian] choreographer Crystal Pite. I love her work. She is ballet-based, but for some reason, the topics and the things she tackles are fascinating to me. There is a piece based on The Green Table, and it was a conversation. The dancers and the dialogue were brilliant. Another project she did having to do with schizophrenia, I saw she has an unbelievable voice. There is a sense of embodiment that is powerful to me.

NAKA Dance Theater in Dismantling: Tactic X | Credit: Robbie Sweeny

Do you experience fear or find it discouraging to think about the future for arts organizations and their ability to achieve increased diversity?

I worry about it. I feel people are talking about equity and social justice at foundations. Some of them talk about non-anti-Blackness. But I find myself invited by organizations to do work, or by foundations giving money to organizations to do POC programming. I am between these organizations and my doing my work. I think if they really want to support artists of color, you need to give money to them directly and not someone in between. It is problematic. A few foundations are giving to organizations to do POC work, and I care and I see that. But they could just give the money to people who can present their own work, not to dance companies and others to present the work.

What about accessibility and arts education for underserved communities? Is the energy for improvement purposeful, or more talk than action?

There are artists and colleagues of mine who are concerned about that. We are talking about taking small but strong steps. Accessibility is expensive but we are trying to articulate the needs. It’s a long way to go. We are hoping there will be one night in every budget for performances that gives money for accessibility and disability needs: justice language super-captions, sign language translators, interpreters, ticket subsidies, all of those things.

When we spoke in 2019, you mentioned San Francisco has lost its color, its courage, its vibrancy. Do you think that is coming back?

It is happening. By having the traumatic experience of the pandemic, by being isolated and inside, I feel there is energy for the emergence of art and art for change. It would be amazing to be having a renaissance like they had in France when everything was so open and people were concerned with life, art, philosophy, and community.

What steps would you like to see large arts organizations and art foundations take to improve the lives of artists but also contribute to the well-being of society, support social justice, preserve cultures and languages threatened with extinction, and other global topics?

[Language preservation] is one of the most amazing things to do right now. We are doing a project with MUA and a Mam community from Guatemala — the Mam community that is the largest outside of Guatemala lives in Oakland. They speak the language, and they bring their cultural clothes and artifacts when they travel, which are important to their identity. Working with them, because they are keeping their language that has existed for centuries from extinction, is vital.

Language is a way of keeping connection. What connects us deeply in terms of our ancestral roots? When we work with these amazing Mam women, I have a sense of hope. We’re talking with them about racism, and they don’t understand the concept. But they understand discrimination. They are being mocked or being put down, and they keep doing what they are doing. For me, this is the sense of resistance. I feel supporting them magnifies how powerful it is to speak in the native language as did their ancestors. I will definitely find hope and seek to support them and other women in the community to continue their dignity. Organizations and foundations can join us in all these things.

José aparece en la revista digital San Francisco Classical Voice

José Ome Navarrete Mazatl / Encuentra arte en comunidad

15 de junio de 2021

por Lou Fancher

José Navarrete Mazatl

Es a principios de junio de 2021 cuando José Ome Navarrete Mazatl y yo logramos concertar una conversación telefónica. Hablamos por última vez en diciembre de 2019 sobre el Festival FRESH 2020 y su participación como co -curador de este festival, programando artistas y activistas Afro-Americanos. Ahora, se encuentra en su ciudad natal, Ciudad de México, donde la falta de recepción del Internet y el alcance restringido de los teléfonos celulares requiere cambio a lugares silenciosos y otros movimientos estratégicos para hacer posible nuestra llamada. Cuando finalmente nos conectamos, nos sorprendemos de la misteriosa paradoja pandémica de que "esto es una eternidad" versus "esto sucedió ayer, ¿no es así?" Si bien ha pasado más de un año sin presentaciones en vivo, esto parece que fuera toda una vida, los recuerdos del FRESH Festival permanecen intactos y, estamos de acuerdo, están “a un parpadeo” en nuestras mentes.

Navarrete Mazatl es un artista multidisciplinario cuyo trabajo se centra en la justicia social. En el año 2001 funda y co-dirige con Debby Kajiyama NAKA Dance Theatre, un colectivo que crea trabajos artísticos experimentales y desarrolla proyectos multidisciplinarios en colaboración con grupos comunitarios basados en la historia de estos grupos, cuentos populares, las mitologías, los rituales y de manera más profética, los problemas actuales de justicia social.

Este mes, Navarrete Mazatl continúa un proyecto de varios años con MUA (Mujeres Unidas y Activas), un grupo de mujeres latinas que abogan por los derechos legales de las trabajadoras del hogar y apoyan a las sobrevivientes de abuso doméstico. Esta colaboración con MUA no ha sido la única buena fortuna de Navarrete durante la pandemia. En 2021, recibió la beca de Guggenheim como coreógrafo, lo que marcó un pináculo en su carrera que, según él, fue completamente inesperado porque su trabajo no es precisamente "coreografía tradicional presentada en un teatro o en un estudio de danza".

Con una nota poco inusual, trágica y personal, Navarrete, al comenzar nuestra conversación, revela que durante la pandemia, aunque no desprecia los honores y las oportunidades recibidas, “Confronte una pérdida inmensa e inconmensurable”. Su madre sucumbió a COVID-19, y sus palabras sobre el impacto de esta pérdida, en lo personal y profesionalmente resuenan mucho después de que concluye nuestra llamada telefónica.

Comencemos hablando de aspectos importantes de tus experiencias durante la pandemia.

Bueno algo tan grande que me pasó es la pérdida de mi querida madre durante la pandemia. Eso fue algo poderoso, emocional y devastador para mí. Fue COVID, sí. Así es como me afectó la pandemia. Tuvimos una relación sólida, larga, muy abierta, amplia amorosa con sus bajos y altos. Es muy difícil su partida, pero me ha permitido contemplar la mortalidad de una manera nueva. Todas estas personas que amamos y que son extremadamente importantes en nuestras vidas ya no están con nosotros. He estado navegando estos tiempos que vivimos con muchas alegrías y mucho dolor, me hace reflexionar sobre mí, sobre mi propia mortalidad. Creo que crecí 20 años más en los momentos posteriores a la partida de mi madre. Todo el mundo de una manera u otra enfrentará esta partida, es una forma de encontrar una nueva forma de navegar la vida. Así es como estoy afrontando la ausencia de mi madre querida.

Durante todo este tiempo de la pandemia mi trabajo se ha enfocado en trabajar con mujeres latinas inmigrantes que buscan el empoderamiento de las trabajadoras domésticas en el Área de la Bahía con Mujeres Unidas y Activas. Ahora estoy aquí en México debido a un proyecto que comenzó hace tres años donde investigamos el fenómeno de la desaparición, de la desaparición forzada. Durante el proceso de creación de esa pieza, estuvimos conectados con familias en México y seguimos en contacto y fortaleciendo lazos con estas familias y otros colectivos que buscan a sus seres queridos.

¿Qué genera para ti internamente este trabajo que estás haciendo en la Ciudad de México?

Para mí, el papel de la mujer en mi vida es muy fuerte y está conectado con mi madre. Mi madre era poderosa y siento que ese es el permiso que tengo para trabajar con MUA. Ella fue una sobreviviente de violencia doméstica - vi a mi madre ser agredida y vi que la golpeaban durante la violencia doméstica entre mis familiares - esa es la relación y mi conexión con MUA. Mi intención es hablar de esa experiencia con el arte para sanarnos, como una estrategia de autocuidado contra el abuso doméstico. Utilizó el movimiento, el teatro, la poesía para dar visibilidad a este grupo en particular. Me interesa mi relación con esta comunidad porque quiero entender el cruce entre estos tres elementos: el arte contemporáneo, la justicia social y la comunidad: estoy usando herramientas artísticas para elevar y apoyar el empoderamiento y la visibilidad de las mujeres latinas.

Saltemos a otro tema completamente diferente: la beca Guggenheim. ¿Cómo te contactaron y qué pensamientos iniciales surgieron?

Fue una gran sorpresa porque nunca esperé conseguir ese premio por el trabajo que hago. No es danza contemporánea tradicional. Utilizo herramientas de coreografía, pero normalmente trabajo con personas que no son bailarinas ni actores de profesión. No estoy creando una hermosa coreografía que se presenta en un teatro o en un estudio de danza. No me interesa eso. ¿Cómo puedo usar mi trayectoria artística para promover una comunidad en particular, quizás una comunidad que se encuentra en los lugares marginales de la sociedad? Eso es lo que me interesa.

¿Significa eso que la definición de coreografía está cambiando?

El concepto de coreografía está cambiando. Las ideas sobre el movimiento se abren, la fuente de expresión llega de otra manera. Cuando me enteré [sobre el Guggenheim], pensé: "Dios mío, me la dieron, no lo puedo creer". Lo he visto en los últimos años, con los galardonados por esta beca y esto es un indicio de que están apoyando nuevas tendencias de artistas y coreografías que no son obras para o de una compañía de danza o grupo de teatro tradicional.

Fue divertido; Primero recibí un correo electrónico que decía que pensaban que yo era finalista, sin embargo, la junta asesora debía aprobarlo, así que me sugirieron no decir nada. No hemos decidido pero es posible que te otorguen la beca. Todavía no parecían seguros. En el segundo correo electrónico, dijeron que me premiaron. Era un tal vez sí pero... luego el segundo correo electrónico lo aclaraban que lo había recibido.

¿Qué fue lo más importante que incluiste en esta solicitud?

El trabajo que sigo haciendo con este grupo de mujeres inmigrantes latinas. Estamos creando escenas fuertes basadas en los testimonios de mujeres latinas que viven en los Estados Unidos. Esa fue mi propuesta. Tenía mucho material en video que refleja este trabajo, así que no necesitaba muchas palabras o detalles para explicarlo. El trabajo es poderoso y en los videos se puede ver el empoderamiento emocional y vigorizante de estas mujeres. Son súper fuertes y poderosas para ayudar a sus propias comunidades.

¿Qué preguntas te gustaría formular, o qué problemas de justicia social optarias para abordar en un nuevo trabajo durante los próximos años?

Definitivamente la relación con las mujeres y otros grupos no normativos, esto es importante para mí. Tener una comprensión equilibrada de nuestro entorno es importante. Me preocupa la violencia de género. Me siento abrumado y trato de abordarlo en mi trabajo como artista. Esta situación de violencia refleja cómo nos relacionamos con nuestra comunidad, nuestra familia, cómo tratamos nuestros recursos potables, nuestra tierra, todas esas cosas de las que nos separamos debido a la forma en que vivimos. No entendemos de dónde vienen las cosas. Especialmente nuestra comida. No tenemos esa preocupación porque todo se nos da. Necesitamos saberlo, porque esta es la razón primordial con la Madre Tierra, con nuestras madres, con las mujeres, con el medio ambiente.

Violencia de género y desapego: ¿Qué prácticas laborales has encontrado para abordar esas separaciones?

Una de las cosas en las que estoy trabajando es cómo puedo cuidarme! Me siento súper inspirado y luego no tengo la capacidad para hacer todo lo que quiero. Me siento abrumado y cansado. Tengo que cuidarme a mí y a mis colaboradores principales. ¡Necesitamos reducir la velocidad de nuestras vidas! Podemos utilizar esta idea de que todo es abrumador por la pandemia, el clima es horrible, la violencia de género es horrible. Y cómo se ve afectado nuestro trabajo. -- Usar el acto radical de desacelerar--, es algo que necesito profundamente hacer, encarnar en mi vida diaria la desaceleración. Está bien reducir la velocidad, pero también debo ser muy claro en mis intenciones. Eso tiene que ver con la contemplación. Tiene que haber otra forma de interactuar. Estamos tan ocupados que no nos permitimos decir que no. Permitir encontrar la magia en una cosa simple que me permite impactar algo, grande o pequeño. Plantar una semilla y esperar que florezca, reducir la velocidad es importante para lograrlo. Estoy tratando de averiguar durante la pandemia quién en la comunidad necesita cosas esenciales, como comida y bueno ha eso me enfoco. Eso cambia mis prioridades.

¿Qué significa o implica ser coreógrafo en los próximos dos a cinco años?

Elijo y me gusta mirar la danza que tiene relaciones. Disfruto el espacio artistico con gente de color, artistas que conecten el arte contemporáneo y la justicia social. Eso me llama la atención. Sin ese contexto, no me interesa. Estoy mirando la danza con un lente muy particular. Muchos artistas increíbles de comunidades no representadas, necesitan apoyo. Me emociono porque esta es la próxima generación. Mi coreografía está diseñada de una manera particular. No veo ballet en este momento. Excepto que hay una coreógrafa [canadiense] Crystal Pite. Me encanta su trabajo. Ella trabaja con el ballet, pero por alguna razón, los temas y las cosas que aborda me fascinan. Hay una pieza basada en The Green Table y fue una conversación. Los bailarines y los diálogos sonoros fueron geniales. Otro proyecto que hizo, que tenía que ver con la esquizofrenia, fue visual y corporalmente increíble. Hay un sentido de encarnar las emociones en el cuerpo que es poderoso y ella lo hace en su trabajo.

¿Te resulta desalentador pensar en el futuro de las fundaciones becarias que apoyan proyectos artísticos y su incapacidad para lograr una mayor diversidad?

Si me preocupa eso. Siento que la gente está hablando de equidad y justicia racial en las fundaciones. Algunos de ellos hablan de no anti-negritud. Pero me he dado cuenta que estas organizaciones, que la mayoría de sus trabajadores son blancos y dan dinero a organizaciones artísticas con la misma problemática del personal para que hagan programación de diversidad con artistas de color. Esto me ha pasado. Creo que si realmente quieren apoyar a los artistas de color, deben darles dinero directamente y no a alguien intermedio. Es problemático. Algunas fundaciones están dando apoyo directo a artistas y organizaciones de color, eso me importa, y hay cambios pero estos cambios necesitan ser mas recurrentes y estables. Simplemente dar el dinero a artistas y grupos de color y que ellos mismos hagan su propia programacion, no a compañías de danza que quieran diversificar su personal y programacion, esto seria lo mejor.

¿Qué pasa con la accesibilidad y la educación artística para las comunidades desatendidas? ¿Esta energía de mejorar tiene propósito o es más hablar que actuar?

Hay artistas y colegas míos que están preocupados por esto. Estamos hablando de dar pasos pequeños pero contundentes. La accesibilidad es cara, pero estamos intentando articular las necesidades y pedir a todas las fundaciones correspondientes que implemente un presupuesto específico para la accesibilidad en las artes vivas. Queda un largo camino por recorrer. Pero por ahora para nosotros es al menos dar una o dos funciones de accesibilidad por cada proyecto, (lenguaje de señas, subtítulos y audiodescripción) y también dar subsidios de boletos a comunidades en necesidad, todas estas cosas.

Cuando hablamos en 2019, mencionaste que San Francisco ha perdido su color, su coraje, su vitalidad. ¿Crees que volverá?

Creo que sí. Al vivir la experiencia traumática de la pandemia, al estar aislado y dentro, siento que hay energía para el surgimiento del arte y el arte para el cambio. Sería increíble tener un renacimiento como el que tuvieron en Francia en los veintes cuando todo era tan abierto y la gente se preocupaba por la vida, el arte, la filosofía y la comunidad.

¿Qué pasos te gustaría que tomen las grandes organizaciones artísticas y fundaciones para mejorar la vida de los artistas, pero también contribuir al bienestar de la sociedad, apoyar la justicia social, preservar culturas y lenguas amenazadas de extinción y otros temas globales?

Para mi es [La preservación del idioma] es una de las cosas más asombrosas que se pueden hacer en este momento. Estamos haciendo un proyecto con MUA y una comunidad Mam de Guatemala - Esta comunidad Mam es la más grande fuera de Guatemala y vive en Oakland. Hablan su idioma ancestral y traen su ropa y artefactos culturales cuando emigran y son elementos importantes para su identidad. Trabajar con ellos es toda una inspiracion, porque mantienen su idioma como resistencia cultural contra la esclavitud, el colonialismo y el progreso urbano por mas de 5 siglos. Esto es maravilloso y vital. El lenguaje natal, maternal es una forma de mantener la conexión, qué nos conecta profundamente en términos de nuestras raíces ancestrales. Cuando trabajamos con estas increíbles familias, especialmente las mujeres Mam, tengo un sentido de esperanza. Estamos hablando con ellas sobre el racismo y no entienden el concepto. Pero entienden la discriminación. Se burlan de ellas o se les menosprecia, y siguen haciendo y manteniendo sus raíces culturales. Para mí, este es el sentido de resistencia, apoyar lo poderoso que es hablar el idioma ancestral como lo hicieron sus antepasados. Definitivamente hay esperanza y me adhiero a la resistencia de ellas, de su comunidad para que continúen con este trabajo de siglos. Esperemos que las organizaciones y fundaciones artísticas y de trabajo social se solidaricen a esta lucha del poder de la mujer latina trabajadora e indigena aqui en el área de la bahía.

ホセ・ナヴァレテ=マサトル:コミュニティーの内にアートを発見する

ルー・ファンチャー/文

José Navarrete Mazatl

ホセ・オメ・ナヴァレテ=マサトルと電話で話ができたのは2021年6月上旬のことであった。その前に彼と話したのは2019年12月で、その時は2020 FRESH Festivalと、彼が共同キュレーションを担当した、黒人女性ダンス・アーティストやアクティビスト出演の週末のパフォーマンスイベントについて語り合った。現在、彼は地元であるメキシコ・シティーに滞在中で、不安定なネット回線や携帯電話の電波制限のせいで、私と電話で話すために場所を移動するなど様々な手段を取らなければいけなかった。ようやく電話がつながった時、私たちはパンデミック・パラドックス、つまり「ずいぶんと時間が経ったね」と「あれって、たった昨日の出来事のように感じるね」という、相反する時間感覚が同時に押し寄せてくるという奇妙さに驚きを覚えた。最後にライブ・パフォーマンスを鑑賞してから一年以上が経ち、それはまるで前世のように遠い昔に感じるが、FRESH Festivalの記憶は「ほんの一瞬しか経っていない」ように今も鮮明である。

ナヴァレテ=マサトルはソーシャル・ジャスティスを軸にした多分野の表現活動を行うアーティストである。デビー・カジヤマと共にNAKA Dance Theaterを創立し、共同ディレクターを勤めている。NAKA Dance Theaterは、実験的なパフォーマンスやコミュニティーを基盤とした共同的かつ多分野的プロジェクトを行うコレクティブである。同コレクティブのプロジェクトは、歴史、民話、神話、儀式から題材を得ており、先見的なアプローチで現在のソーシャル・ジャスティスの問題を扱っている。

今月、ナヴァレテ=マサトルは、ドメスティック・ワーカーの法的権利を主張し、DV被害者の支援を行うラティーナ女性のグループであるMUA (Mujeres Unidas y Activas)との長年にわたるプロジェクトを継続している。パンデミック下でナヴァレテ=マサトルがつかんだ幸運は、MUAとのコラボレーションの継続にとどまらない。2021年、彼は振付師としてグッゲンハイム・フェローシップを受賞した。「オペラ座で披露するような『美しい』振り付けを作っているわけではない」と語る彼自身にとって、受賞は思いがけず彼のキャリアの最大の功績となった。

その輝かしい功績とは裏腹に、パンデミックでの彼の私生活は深い悲しみに覆われていた。表彰や与えられた機会に感謝しているものの、同時期にあまりにも大きな存在を失った。彼はCOVID-19により母を亡くした。その悲しい別れが私生活と仕事に与えた影響を語った彼の言葉は、電話を終えた今でも私の頭の中で響いている。

まず、パンデミック下であなたが経験した重大な出来事についてお話しましょう。

どうしましょう。あまりにも大きいです。実はパンデミックで母が他界しました。私にとって非常に強烈で、悲しく、心を打ちのめす出来事でした。はい、原因はコロナに感染したからです。パンデミックはこのようにして私を苦しめました。母とは長年にわたり培ってきた深い絆がありました。母の死を機に、私は死の捉え方を一新しました。私たちは愛する大切な人との別れをたくさん経験しました。今はこの状況を乗り越えようとしています。自分自身と向き合っています。母が他界してから20年、歳を取ったように感じます。誰もがいつか迎える別れに直面し、人生の生き方について考え直させられました。困難との向き合い方には様々なレベルがあります。

仕事の面では・・・MUA とともにベイ・エリアでドメスティック・ワーカーの権利のために戦うラティーナ移民女性たちと仕事をしていて・・・私は現在メキシコにいます。3年前に始めた、強制失踪を調査するプロジェクトを進めています。この作品の制作中に、メキシコにいる(被害者)家族と出会いました。

今メキシコ・シティーで行っている活動は、どのような内面的な変化をもたらしましたか?

私の人生において女性の存在はとても大きく、母と深いつながりがあります。私の母はとても強い方で、MUAと活動できるのも母の存在が大きいと感じています。父は暴力を振るう人間で、母が殴られたり襲われたりしているのを目撃していました。DVサバイバーとしての経験が私とMUAをつなぎました。その経験をアートと組み合わせ、家庭内暴力被害からの癒しや自己ケアを目指しています。今は所作、演劇、詩を通してMUAの存在を可視化するために活動しています。現代アート、ソーシャル・ジャスティス、そしてコミュニティーの交差点を理解したいと考えており、このコミュニティーとの関係は個人的に大変興味深いものです。これらの三つの要素はどれもラティーナ女性のエンパワメントと可視化を達成するための芸術的なツールです。

話題が飛びますが、次にグッゲンハイム・フェローシップについてお話いただけますか。どのように第一次選考通過の連絡をうけ、受賞についての第一印象などはいかがでしたか?

とても驚きました。私の活動がまさかこのような賞を受賞するとは思いもよりませんでした。なぜなら私の作品は、伝統的なコンテンポラリーダンスではないからです。コリオグラフィーの手法を利用していますが、普段はダンサーや演者ではない方々と活動しています。さらに、私の振付はオペラ座で公演されるような美しいものではありません。私はそういったものには興味がありません。どうすれば自分のアート活動を特定のコミュニティー、例えば社会の周縁に置かれたコミュニティーの社会的地位の向上に利用できるだろうか?そこに興味があります。

それは、コリオグラフィーの定義が変わっているということでしょうか?

コリオグラフィーの概念は変わってきていますね。ムーブメント(所作)についての概念もどんどん広がっており、表現の源が従来とは違う形で湧きあがってくるのです。グッゲンハイムの話を聞いた時、「私に(賞を)くれるなんて信じられない」と思いました。私の受賞は、近年、彼らが伝統的なダンス・カンパニーやシアター・グループの以外のコリオグラフィー作品やアーティストを支援していることの現れです。受賞の連絡からの一連のプロセスは面白いものでした。最初は私がファイナリストであるというメールが来たのですが、まだ委員会の承認を得ないといけないので口外しないでくださいという内容でした。「まだ決まっていないけど、もしかしたら受賞するかもしれない」と言われたので、彼らもまだ確信がないようでした。二通目のメールで受賞したことがわかりました。最初はもしかしたら、という感じで、二回目で確定しました。

グッゲンハイム・フェローへの応募の際、あなたが最も強調したことはなんでしたか?

応募の申請書では、ラティーナ女性グループMUAとの活動内容を紹介しました。アメリカ合衆国で暮らすラティーナ女性たちの証言をもとに真に迫るパフォーマンスを創作していることを強調しました。このグループとの活動を記録した映像資料がたくさんあったので、あまり補足する必要はありませんでした。作品はとてもパワフルで、映像では女性たちの感情深く爽快なエンパワメントを見て取ることができます。彼女たちはとても力強く、自分たちのコミュニティーを助けています。

今後数年間、制作に取り組みながら自らに問いかけてみたいこと、または向き合いたいソーシャル・ジャスティスの問題はありますか?

私は、自分と女性との関係性や、ほかのジェンダーとの関係を非常に重要視しており、バランスの取れた理解も大事だと考えています。これは、私たちが周りの環境とどのように関わり合うかを反映しています。私はジェンダー暴力の問題が大変気がかりです。これは圧倒されるほど深刻な問題で、私はアーティストとして何をすべきか模索しています。(ジェンダー暴力は)私たちがコミュニティーと、家族とどのように関わっているか、また水や土地をどのように扱っているかを反映しています。これらは私たちの(現在の)生き方のせいで生活から切り離されているものです。私たちは、モノがどこから来るのか、特に食べものがどこから来ているのかを理解していません。すべてが与えられているため、そのことを気にもとめませんが、知る必要があります。なぜなら何かを育てることは、母なる大地、私たちの母、女性、環境と関係しているからです。

創作活動においては、ジェンダー暴力や孤立といった分断と向き合うためにどのような実践法を見出しましたか?

私が現在考えていることの一つは、どのように自己ケアを行うかということです。例えば、心が躍るアイディアを思いついたとしても、それを全て自分一人で行うキャパシティが足りないことに気付きます。そうするとひどく気分が沈み、疲れを感じてしまいます。そのため、自分自身と活動に協力してくれる仲間たちを十分にケアする必要があります。ペースを落とす必要はあるのかと自分に問いかけます。全てに圧倒されている状況―パンデミック、最悪な気候、悲惨なジェンダー暴力―を(制作のエネルギーとして)活用できないだろうか。この状況は仕事にどのような影響を及ぼすのだろうか?こういったことを考えつつ、スピードを落とすというラディカルな行為は、私にとって、自分の身体性と行動を結びつけるためにとても必要なことです。

ペースを落とすことに問題はありませんが、それと同時に自分の意思や意図をはっきりさせることも必要です。それは熟考することと関係しています。私たちは何事にも「できない」とは言わないため、常に多忙です。しかし、どんなにシンプルなことでも、もしそこに何かインパクトを与えられる魔法を見つけられたなら、または、何かが実るかもしれないという希望を宿した種を植えることができるのなら、それを成し遂げるためにスピードを落とすことは重要です。パンデミック下では、私のコミュニティー内で誰が具体的に何を必要としているのかを把握しようとしています。例えば、食糧とか。こういったことによって私の活動の優先順位は変化します。

これからの2年から5年の間、振付師として活動することはどのような意味を持ち、どのような役割を担うと思いますか?

私は関係性を題材としたダンスを鑑賞することが好きで、こういったテーマのものを選びます。また、有色人種の方々や、現代アートとソーシャル・ジャスティスをつなぐアーティストに惹かれており、そういった方々を探しています。その文脈なしではあまり興味が湧きません。私は特殊な視点からダンスを捉えています。支援を必要とする素晴らしいアーティストは数多くいます。彼らは次世代を担う存在なので彼らの活躍に期待しています。私のコリオグラフィーの制作方法は独特です。最近はバレエを鑑賞しませんが、一人だけ、クリスタル・パイトという(カナダ人の)振付師に注目しています。彼女の作品が大好きです。彼女の作品はバレエをベースにしていますが、何故だか彼女が取り組むテーマはとても興味深いのです。ザ・グリーン・テーブルをテーマにした作品があるのですが、それは会話を中心とした作品でした。ダンサーも台詞も明快でした。彼女が取り組んだプロジェクトの中には統合失調症を題材としたものもありました。その作品では、彼女が素晴らしい声の持ち主であることを知りました。彼女の声による統合失調症の体現化は、力強く私の心に響きました。

アート団体の将来や、多様性を高めることを考えたときに不安になったり悲観的になったりしますか?

不安はあります。アート団体や財団内で公平性やソーシャル・ジャスティスの話をする人はいます。具体的に反黒人差別を掲げる個人や団体もいます。私はそういった団体や、有色人種を対象としたプログラムに経済支援をしている財団に招致されて仕事をすることが多いです。このような仕事では、私は団体と表現者としての実践との間で板挟みになっています。しかし本当に有色人種アーティストを支援したいのなら、仲介者ではなく彼らに直接お金をあげる方が効果的だと思います。そこに問題があります。有色人種を対象とした活動を行う団体を援助する財団もあり、そういった援助が大事なことであるとは理解していますが、ダンス・カンパニーなどの第三者に資金を渡してアーティストの代わりに作品を発表させるよりも、自分の作品を自ら発表できる人々には直接資金を提供すべきだと思います。

では、十分な社会的支援を受けられずにいるコミュニティーのためのアクセシビリティーやアート教育の状況はどうでしょうか?改善に向けた動きに意義はありますか?行動よりも机上の議論の方が多いですか?

この問題に関心を寄せるアーティストや同業者がいます。私たちは小さくも力強い一歩を踏み出すことについて議論しています。アクセシビリティーを向上するにはお金がかかりますが、私たちはそのニーズを明確に表現しようとしています。まだまだ長い道のりです。将来的には、全ての公演の予算に、アクセシビリティーや障害者のニーズに対応するための資金を確保できるようになることを期待しています。例えば、ソーシャル・ジャスティスを適切に意識した表現での字幕機能、手話通訳、他言語通訳、チケットの補助金などです。

あなたと2019年に話したとき、サンフランシスコはその特色や勇気、活気を失ったとおっしゃっていました。これらは戻ってきましたか?

はい、新しい変化は起こっています。パンデミックによってトラウマを感じ、自粛により室内で孤立していたことから、アートに対する期待や変化をもたらすアートのエネルギーが生まれているように感じています。かつてのフランスのように、様々なものが開放的で寛容な時代を迎え、人々が人生や芸術、哲学、コミュニティーに関心を持つようなルネッサンスが到来すれば素晴らしいと思います。

大規模な芸術団体・財団については、アーティストの生活向上だけではなく、社会貢献、ソーシャル・ジャスティスの達成に向けた支援、絶滅の危機に立たされている文化や言語の保存など、様々なグローバルな課題について、どのような措置を講じてほしいとお考えですか?

(言語の保存)は今できることの中で最も素晴らしいことです。私は、MUAとグアテマラ出身のマム・コミュニティーとプロジェクトを展開しています。このコミュニティーはオークランドを拠点としていて、グアテマラ国外で最も大きなマム・コミュニティーです。彼らは自分たちの言語を使い、移動する時は民族衣装や文化的工芸品など彼らのアイデンティティにとって重要なものを持参します。彼らの言語は数世紀に渡って伝えられてきたものであり、それを保存するために彼らと活動することは極めて重要です。

言語は「つながり」を保つ手段です。何が私たちを祖先とのルーツと深くつなげるのか。マムの女性たちと活動する時、私は希望を感じます。マムの女性たちと人種差別について話し合っていますが、彼女たちは人種差別という概念を理解していません。しかし差別は理解しています。彼女たちは、どんなにからかわれても、差別されても、行っていることをやめずに続けます。私はこれこそが「抵抗」であると思います。彼女たちを支援することで、先祖と同じ母語で話すことがどれほど力になるかを実感しています。私は希望を持ちつづけてこのコミュニティーや女性たちの尊厳のために支援を続けるつもりです。団体や財団もぜひこの活動に参加していただきたいです。

Japanese translation provided by Artoka (Translator: Kasumi Iwama, Editor: Chika Terada)